- Solar energy blog

- Centralized vs. distributed generation: the balance of Brazil’s solar future

Centralized vs. distributed generation: the balance of Brazil’s solar future

Flavio Lopes

Content

Status of solar power in Brazil

Brazil has steadily been establishing itself as a world leader in renewable energy generation, currently accounting for 7% of the world’s renewable energy output on the global energy matrix, overperforming its expected generation potential. Hydropower, wind power, and growing solar energy production feature heavily in the country’s electrical matrix, but they are looking to expand their renewable energy offerings.

In fact, Brazil is such an exciting force in the green energy transition that RatedPower put together an ebook all about the state of renewables in Brazil in 2022.

As part of expanding its clean energy network, Brazil has been moving increasingly toward solar photovoltaic (PV) energy through a combination of distributed and centralized generation plants.

Let’s look more closely at the solar PV landscape in Brazil and see how they are taking steps towards a green future.

Centralized generation vs. Distributed generation

First, we should define the difference between centralized generation and distributed generation.

Centralized generation is what we typically think of when talking about energy generation. Large power plants in centralized locations produce vast amounts of electrical energy that are transmitted, sometimes hundreds of kilometers, to consumers. These power plants can consist of a single power source (e.g., only solar) or multiple (e.g., solar & hydro or solar & wind).

The size of these plants, typically ground-mounted and between 50 MW and a GW in scale in Brazil, is both their main strength and weakness. They can generate huge amounts of energy but at the cost of also being gigantic pieces of infrastructure. As a result, they cannot be located too close to the population centers they supply with power.

Instead, energy must be transmitted over long distances, leading to high costs and lower efficiency. The size and capacity of these plants also require a high level of initial investment and can take some time to become profitable.

Distributed generation, on the other hand, refers to the generation of energy in smaller, more localized power plants (in Brazil, they typically range from 75 to 500 kW for rooftops systems and 0,5 to 5 MW for ground-mounted systems and are mostly on-grid, which means they are connected to the local power utility using their local grid). These tend to be close to the point of consumption and deliver energy to their local area at medium voltage distribution levels. These power plants typically consist of a single power source (e.g., only solar or hydro).

One of the benefits of this approach is that some of these power plants (those that are off-grid, mostly located in the Northern Region of the country) can work in isolation, protected from any vulnerabilities or instabilities in the grid at large. If the centralized grid (SIN) goes down, local people can still rely on power from their closest power utility. There is also less energy loss via transmission lines since the energy travels far shorter distances than from centralized plants.

What does the future look like for the Brazilian solar energy market?

Now we have an understanding of the differences between the two types of power generation, let’s look at what Brazil is doing in each of these areas and the outlook for the future of photovoltaic energy generation.

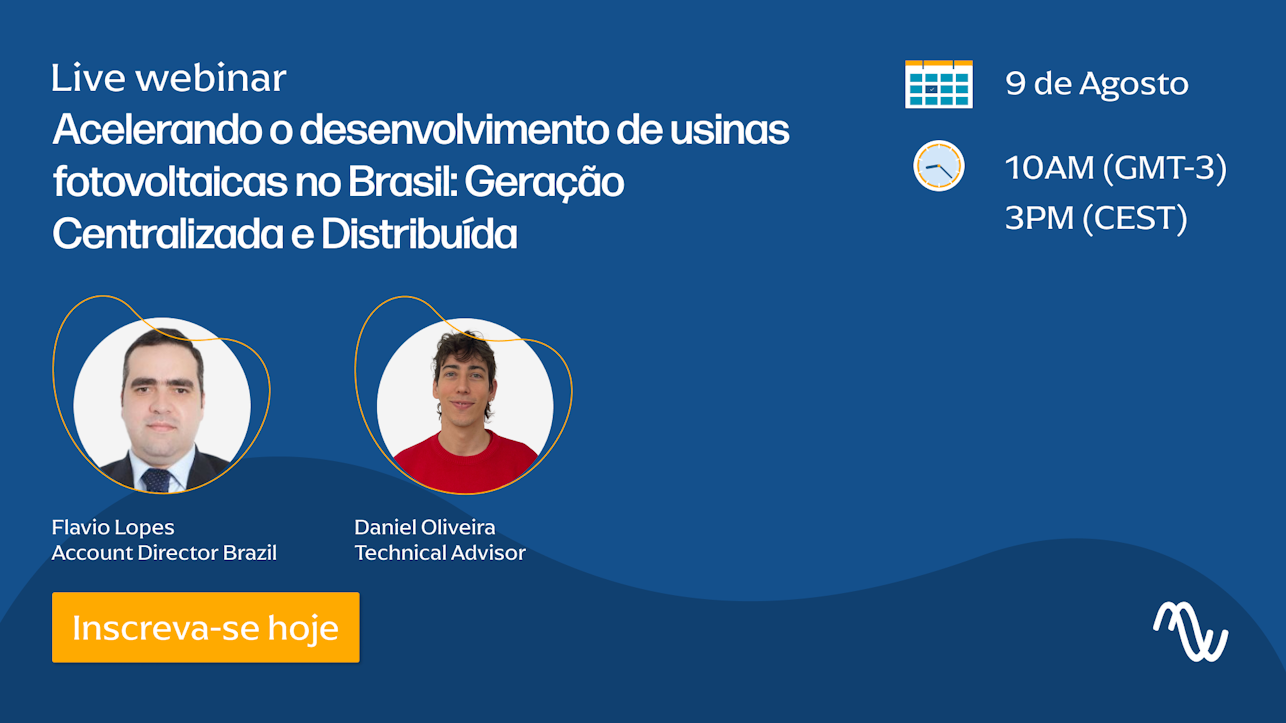

If you're interested in learning more about the Brazilian solar energy market, check out our webinar "Desenvolvimento de usinas fotovoltaicas no Brasil", where two RatedPower energy experts will dive deep into the topic.

Centralized generation of solar energy: Brazil

Since the end of 2022, Brazil has added 3 GW of solar installed capacity, to take it to a total of 27 GW of installed capacity. Most of this capacity, 18.8 GW, is in distributed generation systems, and the remaining 8,2 GW are split between roughly 21,000 centralized plants.

The Brazilian Association of Photovoltaic Solar Energy (ABSOLAR) has projected that there will be a total expansion of 10.1 GW of solar capacity in 2023, with 4.6 GW of this coming from centralized plants. This far outstrips the installed centralized capacity of 2.6 GW in 2022.

This explosion in centralized installations is being supported by a gradual opening of the free market in Brazil. This opening of the market, where energy from renewable sources is being traded at BRL 126/MWh in a four-year contract with supply starting in 2024, has led to PV becoming competitive compared with other renewable sources.

In addition, a 50% discount on tariffs for the use of the transmission and distribution systems came to a close at the end of 2022, meaning there was a late rush to put plans into place before the expiration of this discount. As a result, many large companies have entered into long-term contracts to build new PV projects and increase Brazil’s installed capacity in recent months.

On top of this, centralized plants often take at least two years of development to become operational due to their scale. With the challenges caused by the pandemic, many companies were hesitant to take on new projects. But since the slow return to normal, more companies have thrown their hats into the ring, which is now starting to be reflected in the installed capacity.

Distributed generation of solar energy: Brazil

As mentioned earlier, distributed generation currently accounts for the majority of Brazil’s PV capacity, with 18,801 MW capacity across nearly 1,8 million micro- and mini-generation systems (75 kW up to 5 MW). Like its centralized counterpart, distributed generation is expected to boom in 2023, with a projected addition of 5.6 GW.

If you would like to examine the advantages, challenges and optimization of small PV plants listen to this insightful webinar taken by two RatedPower experts discussing what you would need to consider when approaching smaller scale PV plants

This expansion in distributed capacity is being supported in part by recent legislative changes in Brazil. The Brazilian Electricity Regulatory Agency (ANEEL) recently unanimously approved the regulation of Law 14,300, which affects the law surrounding distributed micro- and mini-generation in Brazil.

This regulation resolved several issues with the current framework, namely concerning the following:

Measurement systems.

Creation of deadlines in cases of power utilities.

Prohibition of the division of the power plants to fit into DG rules/benefits.

Guarantee of faithful fulfillment.

Frequency for changing the members of shared generation.

Rejection of projects, with fixable defects, by power utilities

With this regulation removing many things seen as a hindrance to the sector, Brazil is now in a position to significantly expand its distributed generation capacity. Law 14,300 was already good news for distributed generation, with more than 780,000 micro- and mini-connections being made since its signing. But with these pending issues now resolved, distributed generation in Brazil is in an even stronger position moving into the future.

Brazil is making great strides towards becoming an even greater power on the global renewable stage, thanks to a combination of centralized and distributed solar PV generation. The future looks green for Brazil!

For more insights and information about everything to do with renewables, check out the RatedPower resources page!

Latest stories

Related posts

Market analysis

Defrosting the frozen Nordic solar market

Explore the Nordics’ solar grid challenges and energy transition strategy. Read the blog to uncover policy gaps and solutions shaping Europe’s green future.

Updated 8 JUL, 25

Market analysis

U.S. solar manufacturing grows fourfold, thanks to Inflation Reduction Act

Find out more about the Inflation Reduction Act and how it has increased U.S. solar manufacturing capacity fourfold since the legislation passed in 2022.

Updated 24 JUN, 25

Market analysis

Italy’s €9.7 billion plan to boost renewables and reach net zero

Explore a new state aid scheme helping Italy to work toward a cleaner future and investing in onshore wind, solar PV, hydropower, and sewage gas projects.

Updated 10 JUN, 25

- RatedPower

- Solar energy blog

- Centralized vs. distributed generation: the balance of Brazil’s solar future